Soaring fees and charges from recruitment agencies that bring in foreign domestic workers to Hong Kong were identified by domestic helper welfare group Mission for Migrant Workers (MFMW) as one of the reasons why domestic workers’ average pay do not meet general living costs in the city, and at the same time support their families back home.

According to the concerned group’s survey, over one-third of the domestic helpers’ income goes to payment of loans and agency fees — more than twice the amount paid some five years ago, as reported by South China Morning Post.

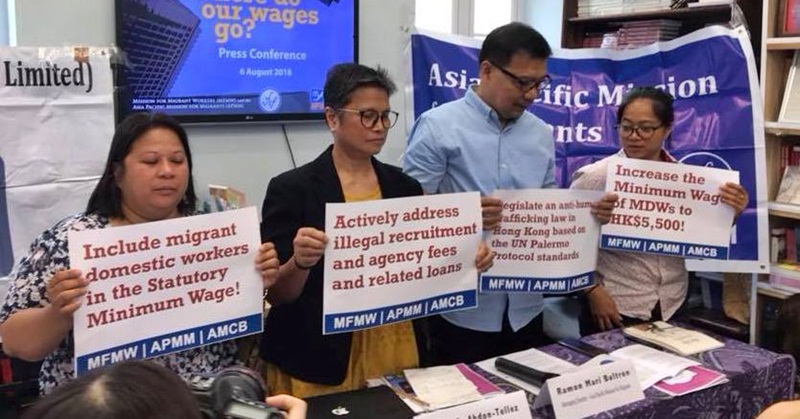

25 Percent Raise Pushed by HK Domestic Groups

Added with the (higher) daily cost of living in the city, domestic helpers are left with smaller remittances and savings as compared before, with an average of HKD 1,700 (USD 218) per month in 2017, or 32 percent of their total earnings, down from 54 per cent five years ago.

The figures shared by MFMW and the Asia Pacific Mission for Migrants (APMM) were gathered from interviews of over 1,000 Filipino domestic helpers back in 2017. This was a follow-up to a similar study conducted five years ago.

The results prompted the concerned migrant workers’ groups to meet with the Labour Department last Aug. 7 (Tuesday) wherein they shared their planned proposal of a 24.7 percent pay raise, which means that the helpers’ minimum monthly earnings will go up to HKD 5,500 from HKD 4,400, explained Cynthia Abdon-Tellez, General Manager of MFMW.

Abdon-Tellez further shared that while the primary goal of these foreign domestic helpers (FDH) who come to Hong Kong is to support their families, they end up spending most of their earnings in Hong Kong, too, and thus, they steadily contribute to the economy of the country in the process.

Drawing a comparison to show how much has changed with the spending choices and budget allocation of FDHs from five years ago, the MFMW disclosed that payment of loans and other related agency fees accounted for 36 percent of FDHs’expenditures in 2017 from 13 percent in 2013. Another 23 per cent went to general living expenses, which include food, clothing, toiletries, accessories, communication, transportation, and donations, as compared to 28.5 percent from five years ago.

MFMW pointed out that one in every ten FDH interviewed in the survey saved a part (around 9 per cent) of their earnings for themselves, which has increased by five percentage points from 2013.

Where do the FDH’s Wages go?

In a similar study conducted by MFMW in April this year, around 50 percent of the respondents shared that they have been charged between HKD 5,000 and HKD 10,000 by agencies to help them work in the city, with some even paying up to HKD 22,000.

The law states that agencies are only allowed to charge up to 10 percent of the FDH’s first monthly earnings. However, some agencies get around this rule by making the helpers sign loan agreements authorized by finance companies they are affiliated to. These documents are typically signed in the helpers’ home countries to avoid regulation and supervision by the Hong Kong government.

Along with the recommendation to increase the minimum monthly wage of FDHs to HKD 5,500, other concerned groups have also urged the Hong Kong government to increase the helpers’ food allowance from HKD 1,037 to HKD 2,500.

The Philippine Consul General in Hong Kong, Antonio Morales, has also backed these requests, which were first brought up by helper representative groups at a meeting with the Labour Department last August.

During the last five years, the minimum wage of FDHs has seen a steady climb of about 2.5 per cent every year, increasing by HKD 100 per year on average from HKD 4,010 in 2013 to HKD 4,410 up until last year.

At present, there are over 360,000 FDHs working in Hong Kong, based on a government report from last year, including 190,000 Filipinos and 154,000 Indonesians.

Considering what every FDH has to go through to find a decent job overseas, as well as the labour and service they put into the homes and families they take care of, it is only fair and just that their rights be respected and considered by their host government — through the appropriation of wages in line with the rising costs and demands of living and working overseas.